Genesis 21:1-3; 22:1-14

The Lord dealt with Sarah as he had said, and the Lord did for Sarah as he had promised. Sarah conceived and bore Abraham a son in his old age, at the time of which God had spoken to him. Abraham gave the name Isaac to his son whom Sarah bore him.

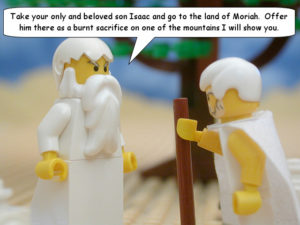

After these things God tested Abraham. He said to him, ‘Abraham!’ And he said, ‘Here I am.’ He said, ‘Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt-offering on one of the mountains that I shall show you.’ So Abraham rose early in the morning, saddled his donkey, and took two of his young men with him, and his son Isaac; he cut the wood for the burnt-offering, and set out and went to the place in the distance that God had shown him. On the third day Abraham looked up and saw the place far away. Then Abraham said to his young men, ‘Stay here with the donkey; the boy and I will go over there; we will worship, and then we will come back to you.’ Abraham took the wood of the burnt-offering and laid it on his son Isaac, and he himself carried the fire and the knife. So the two of them walked on together. Isaac said to his father Abraham, ‘Father!’ And he said, ‘Here I am, my son.’ He said, ‘The fire and the wood are here, but where is the lamb for a burnt-offering?’ Abraham said, ‘God himself will provide the lamb for a burnt-offering, my son.’ So the two of them walked on together.

When they came to the place that God had shown him, Abraham built an altar there and laid the wood in order. He bound his son Isaac, and laid him on the altar, on top of the wood. Then Abraham reached out his hand and took the knife to kill his son. But the angel of the Lord called to him from heaven, and said, ‘Abraham, Abraham!’ And he said, ‘Here I am.’ He said, ‘Do not lay your hand on the boy or do anything to him; for now I know that you fear God, since you have not withheld your son, your only son, from me.’ And Abraham looked up and saw a ram, caught in a thicket by its horns. Abraham went and took the ram and offered it up as a burnt-offering instead of his son. So Abraham called that place ‘The Lord will provide’; as it is said to this day, ‘On the mount of the Lord it shall be provided.’

MESSAGE

I don’t like this story, and that is putting it mildly… I would like to skip it altogether and I tried to find ways to not talk about it directly… but here I am, here we are facing this story that I feel has been so wrongly held up as a wonderful example of faith…

Struggle along with me… as we explore the challenge to Go Sacrifice

Isaac, — the long awaited for son— of Abraham and Sarah, is to be put to death, simply to test the faith of Abraham?

Imagine Isaac, about 13 years old, going on a hike with his dad.

Not only is he clueless about the danger that awaits, chattering on about this and that and making sounds as he fights imaginary enemies, his dad actually puts the firewood that will burn his young body on Isaac’s own, skinny, pre-pubescent back. Unbelievable!

There are a few different ways to read this stories.

The one that brings the most relief is to read it as metaphor, mythical explanations, made-up descriptions of how things came to be the way they are.

This isn’t a stretch, because it’s what, in fact, these stories were.

We can read the sacrifice of Isaac, and really, a lot of the carnage in the Old Testament, as a gloss on the many ethnic cleansings on the Jewish people through the ages, an explanation for why the line must remain ethnically pure, the people absolutely faithful to the Lord, the God of Israel, lest they disappear forever.

And we could even see Sarah’s ability to get pregnant at the age of 90, as a foreshadow of the rise of IVF in the late 21st century.

All this clever literary criticism might help us to feel better, feel as if we are living in a safe house of metaphor instead of in the painful reality of a world where women are demoted when they are infertile, where children are still exposed on mountaintops or thrown into dumpsters, where child abuse and genocide still routinely happens.

Another answer to the texts of terror, as they have come to be known since my OT Professor at Union, feminist theologian Phyllis Trible published a book of that name in 1984,

Another answer is to say that for us Christians, the whole Old Testament exists as a counter for the New Testament—like, isn’t it amazing what God has done?

How good of God to change God’s mind, to stop all that senseless violence, to stop it in the very body, the self-giving death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, all that nonsense come to an end at last.

God is good. All the time. Except before 33 A.D.

But that is pablum Christianity, and anti-semitic as well: to leave the God of wrath to the Jews, marry violence to their view of history, and to end up with Jesus, sweet of face, bouncing children on his knee.

It’s not honest, and it’s not true. Phyllis Trible says “to contrast the Old Testament God of Wrath with the New Testament God of Love is fallacious. The God of Israel is the God of Jesus: in both testaments, there is tension between divine wrath and divine love.”

Just because God only almost permits the death of two innocent children—Ishmael at the mercy of the elements in the desert, Isaac at the mercy of his father on the mountaintop, doesn’t mean God gets to step in at the last second and play the good guy.

“Oh, Abraham, your faith is sufficient and complete, here’s a substitute.”

God let God’s own son die, painfully, on the cross. The fact that Jesus was resurrected doesn’t take away the pain and humiliation that Jesus experienced.

There are many tacks we could take to excuse God, and they are all worthy.

We could say that the ways of God are inexpicable; we can’t possibly understand the fullness of the mind of God, we just have to trust that God knows what God is doing.

Except I believe that we can trust and love God utterly, and still feel that God has some explaining to do.

We could say that, in a sense, God grew up with us—just as in the Great Flood God realized another nature, and promised never again to destroy humankind by flood (gee, thanks God!),

that God ultimately realized in the person of Jesus that only self-giving sacrifice would ever end the cycle of violence,

that we have also matured, evolved, as a species.

We now have a better view of God.

We could say that all these stories are fallible, told from a human perspective, and that we attribute dark motives to God when they are, in fact, our own.

For all we know, it was Abraham who dragged Isaac up the mountain of his own accord—Isaac, after all, was thirteen, and what parent hasn’t been thrown into a murderous rage at least once by their teenage child?

Perhaps God was saving Abraham as well as Isaac.

But it is not our responsibility to make excuses for God to others, or justify these stories to ourselves.

Perhaps, in the end, the point of these stories is much more basic.

To make us feel, fully and poignantly, the value of each human life.

To prevent us from forgetting Rwanda, Darfur, Dachau,

to force us to bear witness to the continuing reality of all that Sarah and Isaac can still represent:

the aging wife made superfluous by the mistress, the young woman ostracized for possible infidelity while her counterpart is untouched, the bag lady, the young person addicted to opioids with no program available, the refugee, the child dying of diarrhea for lack of clean water in the wilderness.

All of these people are real, not ancient, not fairy tale characters; they live, and they breathe, and they fight, and they die.

We know because we see these people; and we know because we are these people.

Will we be broken open, are we willing to feel what they feel?

Perhaps, Trible suggests, the reason these stories remained embedded in our sacred text is to be a thorn in our sides, a reminder of our own dark natures, until we have finally and completely learned to live together without jealousy, ambition, the eternal violent struggle for resources and land and status.

Some churches have trouble naming what we do on Sunday morning “worship.”

They call it a “Celebration” or “Gathering of Joy.”

All very peppy and upbeat. Except, the thing is, it is not always celebrating that we need to do on Sunday morning.

Sometimes, we need to cry. Sometimes, we need to shake our fists at heaven.

Maybe that’s why these stories are here.

Abraham’s hand trembling above his son, his only son, whom he loved.

I find this story horrible.

Sometimes you just have to face the darkness, and live with the sadness. And yes, sometimes, God does swoop in at the last second to make things come right, or at least, more right than they were.

As someone put it, “everything turns out all right in the end. If it’s not all right, it’s not the end.”

Walter Brueggeman, after he’d read Genesis cover to cover, and tried to make sense of these stories, said, “Faith is nothing other than the trust in the power of the resurrection against every deathly circumstance.”

And maybe, just maybe, the point of these difficult stories in the Bible is to remind us that we do not live in a tame universe, that our God is not a tame God.

The feminist sci-fi novelist, Ursula LeGuin, said it this way:

“Take the tale in your teeth, then, and bite till the blood runs, hoping it’s not poison, and we will all come to the end together, and even to the beginning: living, as we do, in the middle.” Amen

Resources:

The Texts of Terror by Phyllis Trible

Sermon by Rev Molly Phinney Baskette http://www.firstchurchsomerville.org/worship/sermons/view/179

0 Comments